Patterns of Enrolment by Grade and Age

In Sub Saharan Africa many children are overage for the grades they attend. In some poor areas more than half of children are overage by two years or more. In rural Africa it is common to assess school readiness by the size of a child especially where birthdates are unknown. In some of our household samples many children are stunted, almost guaranteeing late enrolment. Repetition of grades is endemic in systems which have low completion rates. This exacerbates the numbers of children overage. Girls are especially disadvantaged by being overage. No high completion system has a wide range of age in grade.

Conventional measures of patterns of access conceal the way age in grade varies (Lewin, 2011d). The evolution of age in grade relationships is important for several reasons. First, children who enrol above the normal age of entry will miss learning experiences at a time when they are most receptive to learning basic skills and establishing secure foundations for cognitive development.

Second, those who repeat Grade 1 or subsequent grades will become overage for their grade. The more overage a child is within a grade the more it is likely that they will underachieve (Taylor et al, 2010).

Third, where older children are taught in class groups with younger children there may be psycho-social issues (e.g. of self esteem, bullying, sexual harassment) and problems of matching learning to cognitive capabilities (especially with monograde curricula where all pupils are taught the same things at the same time).

Fourth, overage children will be late to arrive at the last grade of primary or junior secondary school. Where the age of initial entry is six or seven, primary school leavers in a six grade system will be 12 or 13. If they are two years overage, they will be 14 or 15. This approaches the ages of entry to the labour market and of marriage. It is unlikely most will continue further.

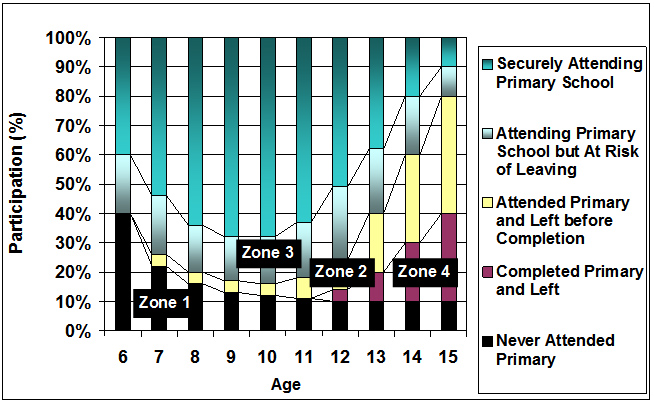

The chart below shows how participation can change with age and is linked to the CREATE zones of exclusion. It indicates that in this system, which is based on data from Ghana, about 40% of six year olds are not in school. This falls to about 10% by age 11. Above this age those who have not enrolled are unlikely to ever enrol (zone 1).

From age 7 and above some children drop out and the number gradually increases with age. These become the largest number of out of school children above 11 years old and fall into zone 2 of the CREATE model. Children who enrol but are at risk of drop out and are characterised as low attending, overage, repeating years and poor achieving fall into zone 3 and gradually become an increasing proportion of those still enrolled in primary grades.

From 12 years and above some make the transition into secondary school though if they fail to do this by the age of 15 or so it becomes increasingly unlikely that they will complete lower secondary successfully.

Age and Zones of Exclusion

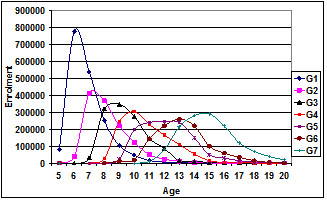

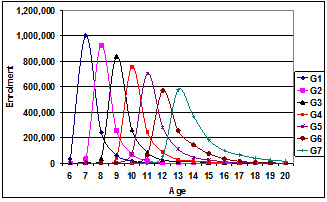

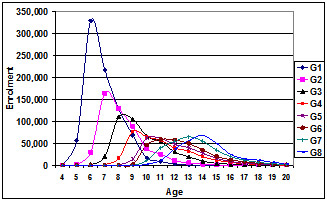

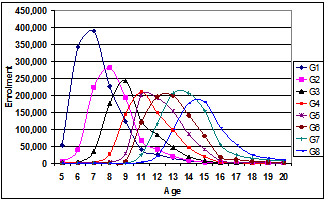

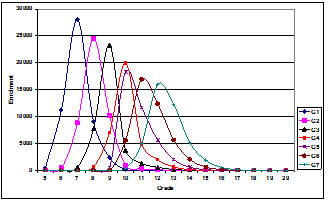

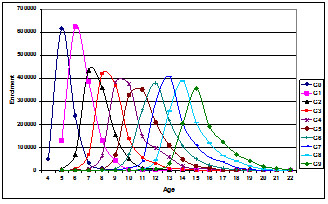

Data on age in grade illustrates common patterns. These are shown below. In Uganda over enrolment in Grade 1 includes children between the ages of 5 and 10 years. Enrolments from Grade 2 to 7 are substantially less and include increasing age dispersion. By Grade 7 the age range is between 12 and 20 years. Similarly Malawi has a pattern of overage enrolment where the spread of ages within a grade increases greatly from Grade 1 to Grade 8. There is even more attrition than in Uganda with only a small minority surviving to Grade 8. Some children in Grade 8 are likely to be over 18 years old and would thus not complete junior secondary until they were well over 20 years old.

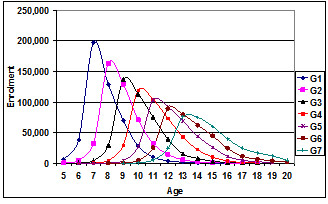

In Kenya age on entry may be as much as 10 or 11 years. By Grade 8 children are between 12 and 20 years old making it unlikely that the older children will progress to secondary school, especially if they are girls. The dispersion of ages increases with Grade making it likely that wide mixed age teaching groups will present a challenge to orthodox monograde pedagogies. Ghana and Zambia have similar profiles to Uganda, Malawi and Kenya with differences in detail. In these countries there is a sequential reduction in enrolments by grade coupled with widening age in grade spread from about five years in Grade 1 to eight years in Grade 6 or 7.

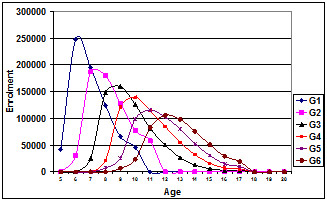

Botswana presents a contrasting picture. Here most children are in the appropriate grade for their age in lower grades. There is some increase in the range of ages but much less than in most of the other countries. Tanzania is more like Botswana than most of the other countries. Here the data indicates that most children are within two years of the correct age for their grade. This is a striking change from the 1990s when the distribution of age in grade in Tanzania resembled other East African countries. South Africa resembles Botswana in its distribution of age by grade. For higher grades there are clearly pedagogic issues since there are children in the xame grade with a six or seven year age difference. The oldest will be over 20 years before compelteing matriculation and the twelfth grade. It is more likely they will drop out not much beyond grade 9.

There are many variations on these patterns across countries. In most cases the dispersion in age within a grade increases with the grade level though primary school. Access to secondary schooling is selective. Often the process tends to select out those who are overage completing primary school since those who are older often have poorer performance. It can therefore be the case that age in grade dispersion is less at secondary level (Lewin and Sabates, 2011). If the age in grade range remains wide it is inevitable that most will not complete primary and junior secondary. All countries or regions which succeed in universalising enrolment and completion of primary and junior secondary have low dispersions of age in grade. Ensuring enrolment and progression on schedule is a low cost lever on participation that offers large gains at modest costs.

Age-in-grade distributions

Uganda

Tanzania

Malawi

Ghana

Kenya

Zambia

Botswana

South Africa

If the age in grade range remains wide it is inevitable that most will not complete primary and junior secondary. All countries or regions which succeed in universalising enrolment and completion of primary and junior secondary have low dispersions of age in grade. Ensuring enrolment and progression on schedule is a low cost lever on participation that offers large gains at modest costs.

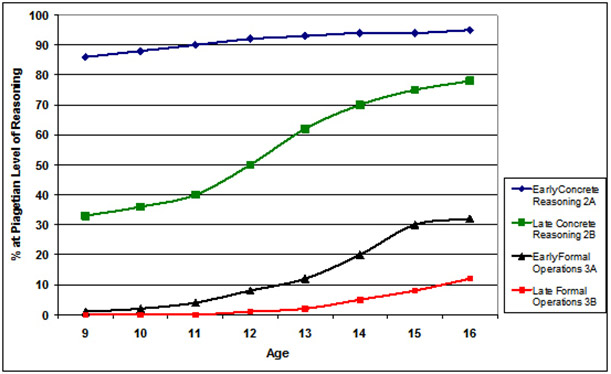

Age in grade is important because children of different ages reason in different ways. Younger children are largely concrete operational. Their reasoning is associative and usually only uses a single dimension. Late concrete thinkers can compensate and order relationships between two variables. Formal thinkers can understand causality with more than one pathway and can use simple models to understand relationships. Late formal thinkers can use abstract models to explore multidimensional relationships and make predictions. In the UK population almost all children can reason concretely though only about 80% are late concrete operational thinkers. About 30% are early formal operational reasoners and only 10% are late formal operational reasoners. In countries where there is a wide range of age in grade the curriculum and pedagogic issues are clear The distribution of capability within an age group will be overlaid by the spread of capability related to age. Monograde curricula and pedagogy will not be best suited to wide ranges in reasoning capability.

Piagetian Stages of Cognitive Development and Age in a UK Population (Shayer et al 1976)