Zones of exclusion in four countries

The zones of exclusion model can be applied at national level. This gives an illustration of how it can be used to conceptualise starting points and key issues. The charts below were constructed in 2007. More recent profiles of enrolment can be found in Lewin 2015 Educational Access, Equity and Development, IIEP, UNESCO Paris and in Lewin K M Educational Challenges of Transition: Global Partnership for Education 2017).

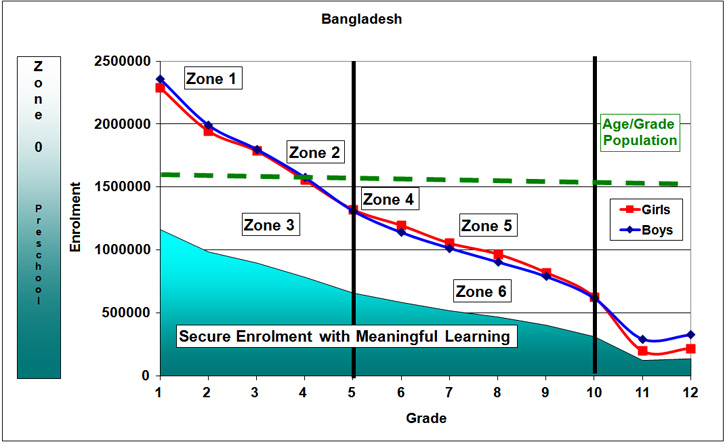

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh there are more children enrolled in Grades 1-3 than there are in the relevant age group. This is indicative of over age and some under age enrolment, and repetition of grades. Enrolment in Grade 1 is consistently about 30% more than it would have been had no child repeated. Above Grade 4 there are fewer children enrolled than in the age group. It is now the case that there are about the same number of girls as boys enrolled, unlike a decade ago when there was a significant gender gap. Bangladesh has a short primary system of only five grades. Its gross enrolment rate is above 100%. However, only 50% of an age group succeed in entering secondary school in Grade 6 successfully and only 15% or so reach Grade 11 and 12 (Ahmed et al 2007).

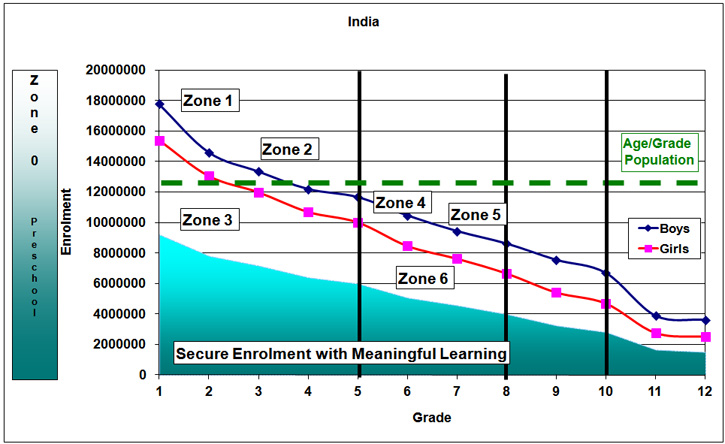

India

The zonal chart for India shows that at national level there are clearly issues that remain despite the gains achieved under India’s large scale EFA programme Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. Less than 60% of children complete Grade 5 on average and no more than 40% succeed in entering Grade 9. Above Grade 3 there are fewer enrolled than there are in the age cohort. There is a large difference in enrolments between boys and girls. The gap widens up to Grade 10 but above this girls drop out less than boys (Govinda et al, 2007). There are fewer girls than boys in the population. In some parts of some states various forms of gendered foeticide and migration result in sex ratios as low as 800:1000. The all India chart conceals the great differences in enrolment patterns between states, especially the low enrolment northern states and those in the south where most children attend secondary school.

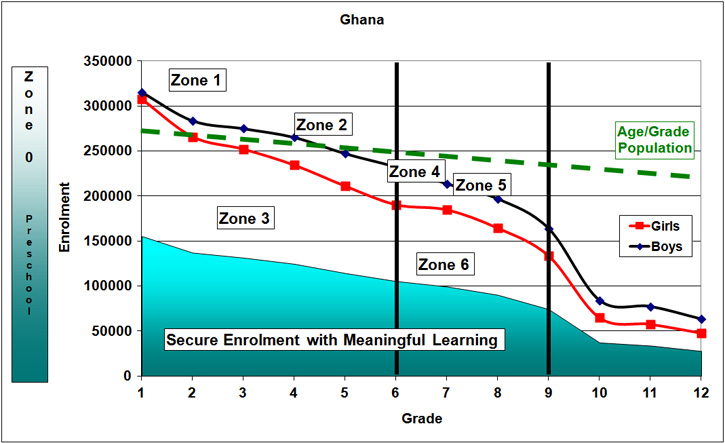

Ghana

In Ghana in the first three grades there are more enrolled than in the age group as in the other countries. Though nearly equal numbers of boys and girls enter Grade 1, girls drop out faster until Grade 6. If they enter junior high school they drop out less than boys (Akyeampong et al, 2007). Above Grade 9 at entry to senior secondary school there is rapid attrition as costs rise and schools become very selective. By Grade 9 less than half the age group is enrolled. Moreover it remains the case that about 75% of all university entrants originate from only 20% of the secondary schools. Most have attended fee paying high cost private schools (Djangmah, 2011). Ghana has a distance to travel to achieve basic education for all. Access is inequitably distributed and quality varies widely.

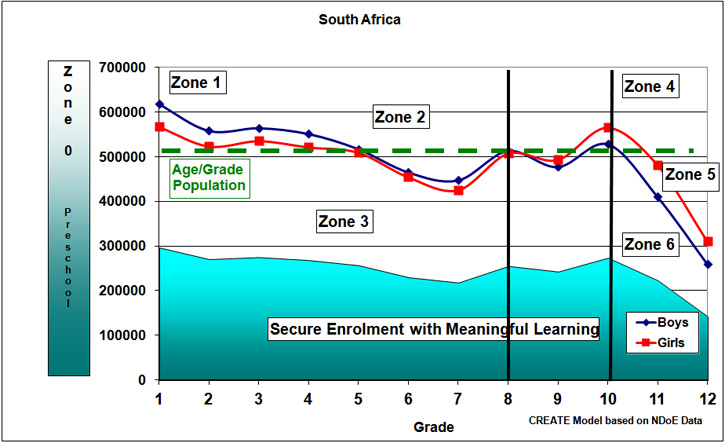

South Africa

South Africa has almost full enrolment of the school age group. The age of entry has been reduced by incorporating a reception year (Grade R) into the normal primary cycle. From Grade 1 to 9 there are as many or more enrolled as there are in the age group. Above Grade 6 there are more girls than boys enrolled which is also the case in several other southern African countries. Attrition accelerates above Grade 9 as students enter the further education and training (FET) level and study for national examinations. Many drop out before completing Grade 12. Below this level progression has been unhampered by selection examinations that block progression of low achievers. Though enrolment is high, achievement is often low (Taylor et al 2010, Motala et al 2011, Gilmour et al 2009).

In all four countries the numbers of children who never enrol are fewer than 10% and may be less than 5% of all children. Most 5-15 year olds claim to be enrolled. Those who are not include those excluded because of their civil status (e.g. illegal cross border/internal migrants) and those made invisible as a result of social exclusions (e.g. social and ethnic group, disability, HIV status, nomads). Those in zone 2 (drop outs) are the greatest number out of school. By Grade 9 more than half the children are no longer in school in three of the countries.

In zone 3 children are enrolled in primary but judged to be at risk. This is signified by low attendance (less than 90% of the school time) over age (two years or more) and low achievement (two years or more behind). In South Africa many children do not attend regularly. Over a third are over age by two years or more in Grade 4. And levels of achievement are often problematic with more than half at least two years behind by Grade 6 (Gilmour et al, 2009, Taylor et al. 2010). In case study schools in Madhya Pradesh in India an average of 35% of students were not in school on the day of the visit by researchers (Bandyopadhyay, Das and Zeitlyn, 2011). In low enrolment rural areas of Ghana, the majority of children in schools are over age by two years or more (Rolleston et al, 2011). In Bangladesh in the rural primary schools surveyed, about half of all students in Grades 1-5 were two years or more overage (Zeitlyn and Hossain, 2011). Indications of poor attendance, over age progression and low achievement are endemic across our field data from schools and communities.

Zone 4 identifies children who fail to make the transition from primary to lower secondary. Transition rates from primary to secondary in all the countries are over 80%. However, in all cases except South Africa so much drop out has already taken place through the primary school grades that no more than 50% enter secondary school. Transition to secondary school often involves travel and additional costs which are a disincentive to continue (Siddhu, 2010). Drop out from secondary (zone 5) can be an important issue. Low achievement and rising opportunity costs linked to income earning employment can lead to drop out before completion. Poor learning achievement of those enrolled in secondary (zone 6) is an issue especially where there are no standardised assessments that allow national monitoring of standards.